Soft tissue sarcoma (STS) is a form of cancer affecting the soft tissue, or support structures of the body. It most often arises in connective tissue such as the tendons, ligaments, fascia, fat, and the synovium of the joints, but can also occur in other soft tissue including nerves, muscles, and blood vessels. Soft tissue sarcoma is rare, comprising about one percent of new cancers.

Overview

- What are soft-tissue sarcomas?

-

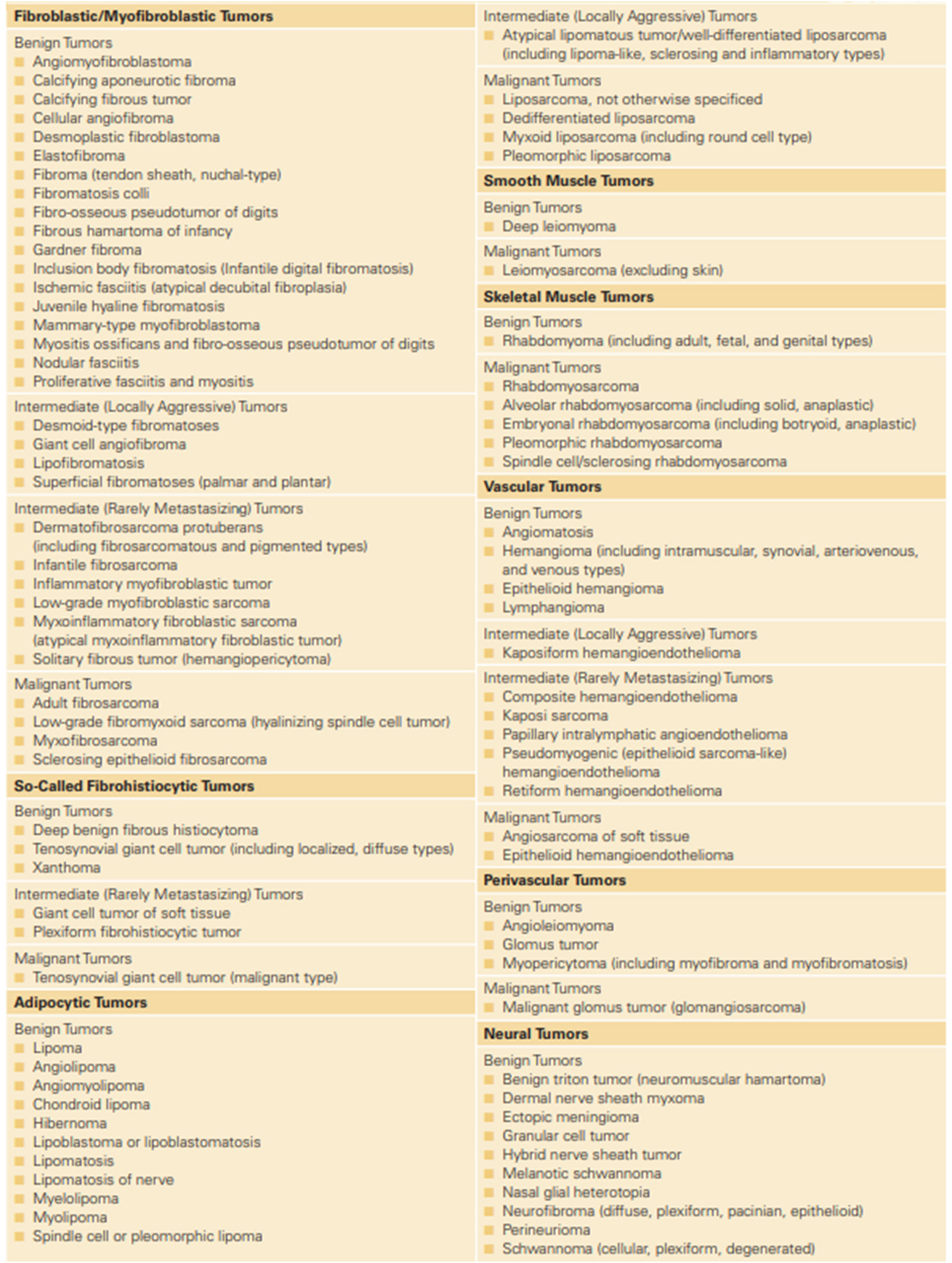

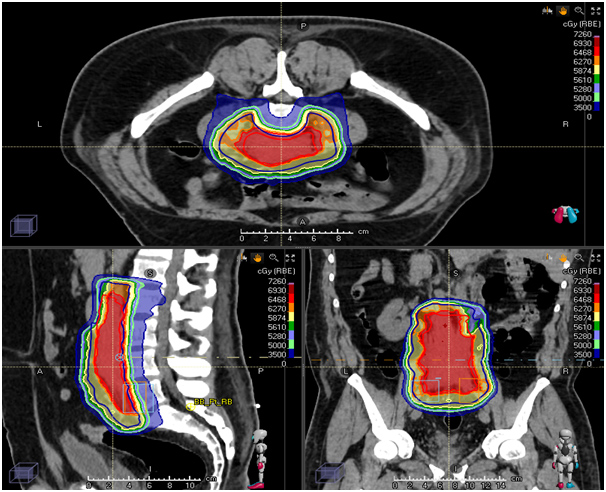

- What are the types of soft-tissue sarcomas?

-

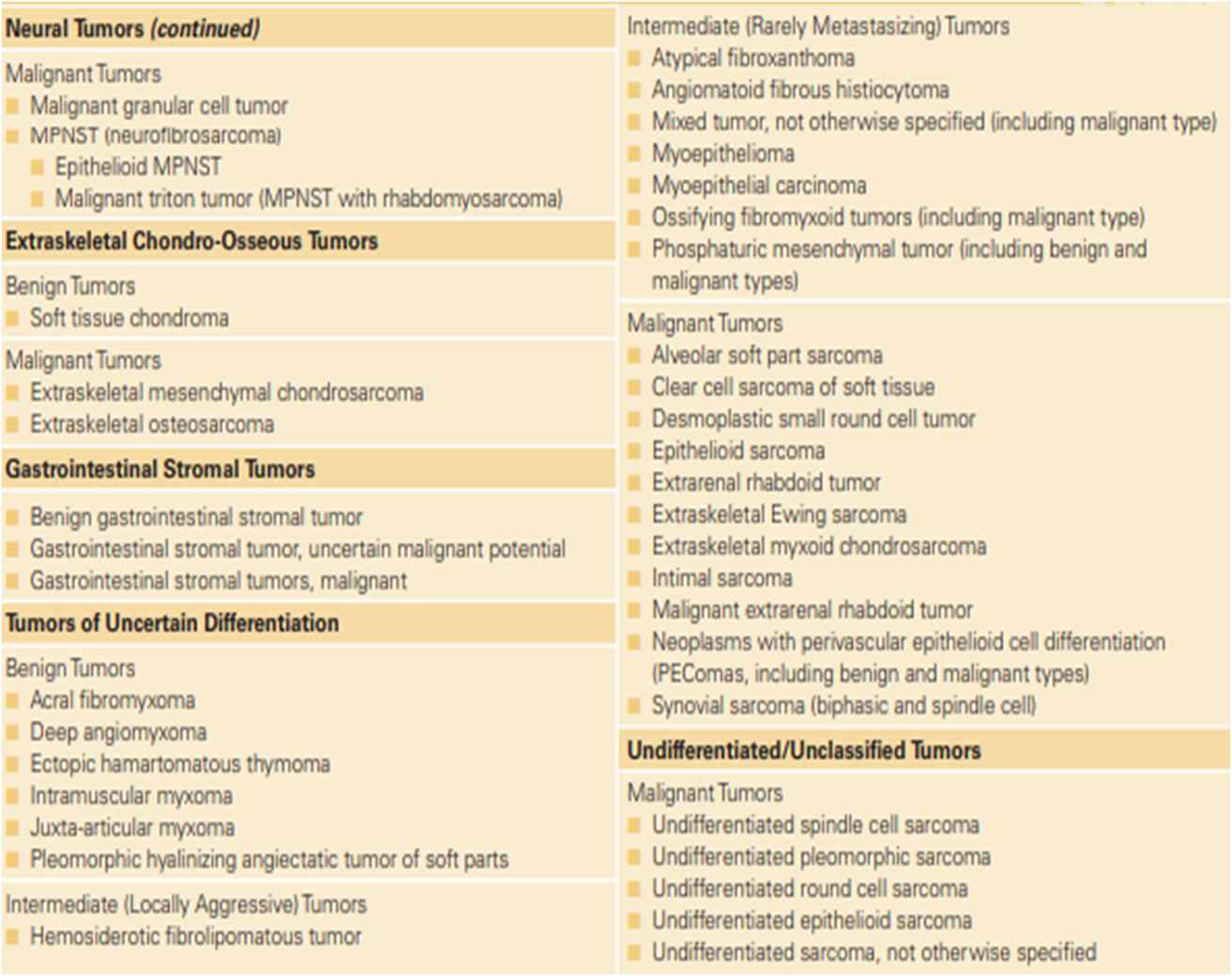

- How are soft tissue sarcomas staged before treatment?

-

Tumours are staged based on extent of primary, extent of regional spread and extent of metastases.

Symptoms

How do patients with soft tissue sarcomas present?

Soft tissue sarcoma often does not cause symptoms in the early stages.

- The first symptom people may notice is a painless lump.

- Sometimes, the lump causes cause pain, soreness, or difficulty breathing if it presses on nerves, muscles, or blood vessels.

- Many people notice soft tissue sarcoma only after an unrelated injury draws attention to that part of the body.

Risk Factors

For the great majority of Soft tissue sarcomas, there is no known etiology. Environmental or genetic factors can be a cause of a minority of STS. Environmental factors can be radiation exposure, chemical exposures (such as vinyl chloride, dioxin, arsenical pesticides), immunosuppression and viruses (human immunodeficiency virus, human herpesvirus type 8). Certain clinical syndromes are associated with a genetic predisposition for the development of sarcoma. A few examples include Li-Fraumeni syndrome and Werner syndrome, which are associated with the development of STS as well as other malignancies; neurofibromatosis type 1, which is associated with the development of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours; and familial adenomatous polyposis (Gardner syndrome), which is associated with the development of abdominal desmoid tumours.

- Biopsy

-

As there are no reliable symptoms or signs that distinguish benign tumours from malignant soft-tissue tumours, it is imperative to biopsy all soft-tissue lumps that persist or grow. In performing a biopsy, the surgeon must place the incision in such a location so as not to compromise subsequent definitive surgical excision. There two common kinds of biopsy for soft tissue lesions.

- True-cut biopsy

- Incisional Biopsy

- Excision biopsy

Although it has recently been suggested that a true-cut biopsy is useful in the diagnosis of soft-tissue sarcomas, it is generally agreed that a large sample of tissue is necessary to assign an accurate diagnosis and grade. The incisional biopsy provides a generous sample of tissue with minimal disturbance of the surrounding tissue planes. Unless a biopsy incision is appropriately sited, proper radical resection of the lesion may be precluded and amputation of an extremity may be the only alternative to ensure adequate treatment.

- Imaging

-

Computed tomography (CT) scanning through the affected region is the most useful radiographic technique in diagnosing soft-tissue sarcomas. It is also used to image chest which is a common site of spread.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also is extremely useful. The contrast between tumour and muscle, and tumour and vessel, is better with MRI than with CT scanning. Arteriography is frequently used to assess the possible involvement and vessel displacement by the tumour.

- PET-CT scan is often done at diagnosis to stage the disease. It is also the investigation of choice to monitor response and to detect disease recurrence.

- Other investigations such as bone marrow examination in pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma.

There are several types of sarcomas. It is strongly recommended for the pathology is reviewed by a pathologist specialized in reporting sarcomas. Results of the biopsy must include:

- Undifferentiated pleomorphic soft tissue sarcoma: although rare, it is still the most common sarcoma in adults. It can occur in any part of the body but is most common in extremities.

- Liposarcoma arises from cells storing fat in deep soft tissue. Most occur in the thigh and upto a third occur in the abdomen.

- Leiomyosarcoma arises from smooth muscles which are found in the organs such as the heart, stomach, blood vessel wall, etc. Essentially they can also occur in any part of the body but most commonly occur in the uterus, limbs and stomach.

- Synovial cell sarcoma usually occurs near to the main joints of arms, legs and neck. It is also known to occur in several other locations.

- Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour arises from the connective tissue around the nerves. These are also referred to as malignant schwannoma or neurofibrosarcoma.

- Angiosarcoma arises from the inner linings of blood vessels and can occur in any area of the body.

- Solitary fibrous tumour mostly involves the pleura which is a covering over the lungs.

- Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberance develops in deep layers of skin and is most commonly found on the torso, but also in arms, legs, head and neck regions.

- Desmoplastic small round cell tumour occurs in adolescents and young adults and generally has an aggressive course. Clinical manifestations are often related to the extensive abdominal disease.

- Rhabdomyosarcoma arises from cells making the skeletal muscles, the muscles one control voluntarily. Ironically it can even arise in areas devoid of skeletal muscles. The most common areas where RMS can be seen are the head neck, vagina, arms, legs and trunk of the body.

- Desmoidtumours also referred to as aggressive fibromatosis are rare tumours that are not technically sarcomas but are grouped because they arise from fibroblasts which are cells found throughout the body providing support and protection to organs such as lungs, liver, heart, kidneys, skin, bowel, etc.

- Grade of tumours

-

Determines how aggressive the sarcomas are. Several grading systems exist and most commonly FNCLCC system is used to grade them as low grade, intermediate grade and high grade.

- Molecular Profiling

-

Since there is a lot of heterogeneity in soft tissue sarcomas, tests to detect molecular or genetic alterations are commonly advised to differentiate one from the other as well as to offer targeted therapies.

Treatment

Planning of the treatment involves a multidisciplinary team* of medical professionals with a high level of experience in the management of these tumours (usually called reference or expert centres). This usually implies a meeting of different specialists, called multidisciplinary opinion or tumour board review. In this meeting, the planning of treatment will be discussed according to the relevant information mentioned before.

The treatment will usually combine therapies that:

- Act on cancer locally, such as surgery or radiotherapy.

- Act on the cancer cells all over the body by systemic therapy*, such as chemotherapy.

The extent of the treatment will depend on the stage of the sarcoma, on the characteristics of the tumour and the risks for the patient.

- Surgery

-

Most frequently, surgery is the standard treatment method used for localized sarcoma. As soft tissue sarcomas are rare, surgery should be performed by a surgeon who specializes in treating them. The goal of most sarcoma surgery is complete resection without leaving anything behind (microscopically negative margins), thereby reducing the risk of local recurrence.

The completeness of the surgical resection can be defined by several terms:

- "RO" resection means complete removal of all tumour according to the analysis of the tissue margins by microscope done by the pathologist;

- "R1" resection indicates that the margins of the resected parts show the presence of tumour cells when viewed microscopically;

- “R2" resection indicates a macroscopic residual disease (a portion of tumour visible to the naked eye).

Small sarcomas can usually be effectively removed by surgery alone. R1 and R2 margins may need additional treatment by surgery; other options are to treat the resected margin containing tumour cells with radiation and possibly chemotherapy.

- Systemic therapy (Chemotherapy/Targeted Therapy)

-

Soft tissue sarcomas have been identified to be of more than 50 types. Most of them have a molecular alteration as which is typical of that type of sarcoma and are used to confirm the diagnosis of sarcoma. For example: Synovial Sarcoma: t(X; 18) (p11.2; q11.2), Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma t (2:13) (q13; q14) etc. The choice of treatment depends on the type of sarcoma. The role of chemotherapy currently is there in both curative and advanced cancer settings.

The current role of chemotherapy for patients who have localized disease is not defined well though there is more acceptance of chemotherapy in high-risk sarcomas like large tumours, high grades and chemosensitivehistologies like synovial sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, etc. Chemotherapy is often considered in combination (ifosfamide+ doxorubicin, docetaxel+ gemcitabine) after surgery in such cases. It may especially be considered in these 2 situations: When the disease is considered to be at high risk of recurrence (i.e. high grade, deep-seated, > 5 cm). In selected cases, preoperative chemotherapy is also given along with radiotherapy to downsize the disease to make it operable. Sometimes hyperthermia with chemotherapy is delivered in certain clinical situations.

Chemotherapy is the mainstay of the treatment of advanced disease, as the drugs administered enter the bloodstream and reach cancer cells throughout the body. These drugs can be given alone or in combination and may be given as an outpatient or as an inpatient with admission to the hospital for a few days. Chemotherapy is given in cycles of treatment and the chemotherapy regimen usually consists of several cycles given over a set period: the number of cycles depends on the type, site and size of sarcoma and how it is responding to the drugs. The most common drug regimen is doxorubicin alone or in combination with Ifosfamide, Docetaxel with Gemcitabine, etc. The common adverse effects are low blood counts, vomiting, alopecia, fatigue and these side effects can be controlled to great extent with proper supportive care medications. In some sarcomas like alveolar soft part sarcoma, and angiogenesis drugs which target VEGF like pazopanib has very good clinical activity and patient attain long term disease control. There are many trials going on in sarcoma treatment as the benefit of chemotherapy is still not optimal.

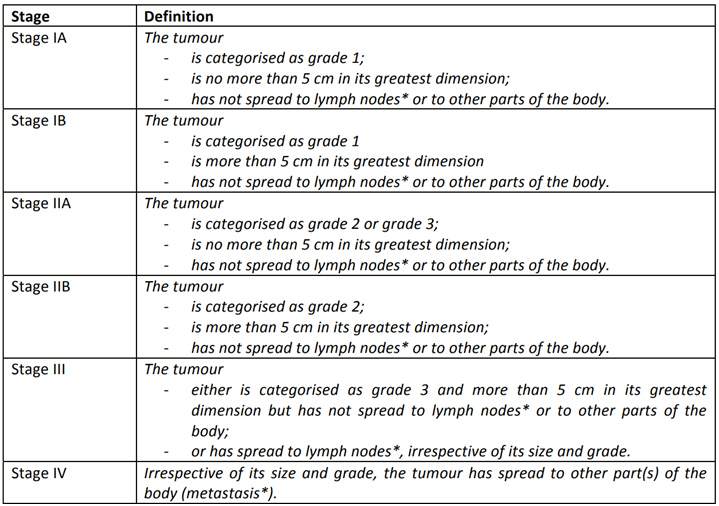

- Radiotherapy

-

High grade, deep-seated tumours larger than 5 cm are often treated with a combination of surgery and radiation therapy; radiation therapy may be used before (neo−adjuvant) surgery (to shrink the tumour size and allow it to be removed completely) or after (adjuvant) surgery (to kill any remaining cancer cells); re−operation may be considered in case of positive margins.

There is evidence to suggest that high precision radiotherapy techniques such as IMRT, VMAT/Tomotherapy can lead to lesser toxicities in patients of sarcoma in most locations.

- Brachytherapy for soft tissue sarcomas

-

Brachytherapy involves the placement of either temporary catheter with radioactive source material inside or permanent radioactive seeds in the resection bed at the time of surgery. These sources are spaced at even intervals to cover the area of potential tumour spread. Brachytherapy may be used as a sole treatment modality, or in conjunction with external beam radiation. An advantage of brachytherapy is that the sources used have steeper dose gradients than those for external beam radiation therapy, minimizing exposure of adjacent tissues to substantial radiation. Besides, treatment durations are generally shorter with brachytherapy than with external beam radiotherapy. It can also be used in patients with local recurrence in a previously irradiated field, combined with surgical resection. However, brachytherapy is not always feasible in patients with difficult surgical anatomy, or those with osseous structures, neurovascular structures, or vital organs immediately adjacent to the tumour.

- Proton therapy for Soft-tissue Sarcomas

-

Proton-beam RT is a treatment modality that has been used for the treatment of skull base and Para spinal sarcomas and is being increasingly used for STS in other locations. The use of protons, rather than the photons used in conventional RT, has the potential to allow substantial dose reductions to adjacent normal tissues. As with IMRT, this modality may be of particular benefit in patients with the retroperitoneal disease, given the adjacent vital structures.

Other Bone & Soft Tissue Tumours

Copyright © 2023 Apollo Proton Cancer Centre. All Rights Reserved